Variance in Commander

By Dr. Michael V. LeVine & Ken Baumann

What is variance? The meaning of the word differs in colloquial language and statistics, but the intersection of these meanings is essentially this: if an outcome is high variance, it will be hard to predict exactly what the outcome will be. In Magic: The Gathering, a high variance game will play out differently every time. A high variance deck could either describe a deck with high variance in its strength (it draws either good or bad hands, not average hands) or high variance in its play patterns (different hands generate very different play experiences and board states). An example of the first would be a deck like Goblin Charbelcher in Modern or Legacy: you have hands that can turbo out a Charbelcher or you don’t. On the other hand, Burn is a low variance deck in terms of strength, as many of the cards are functionally equivalent. Adaptive midrange or control decks can be high variance in terms of gameplay, as cards tend to play very different roles, while decks with a very specific game plan tend to be low variance in gameplay (Belcher is also good example of this, which illustrates how a deck can be low variance in one way and high variance in another).

How do we calculate variance in a game of Magic? Variance in your win percentage is straight-forward! You get to use the same math any gambler would (Krark players: take note!). If you win 50% of the time, your chance of winning is the same as flipping a fair coin, which is the highest variance type of bet. Even though you win the flip 50% of the time, you don’t get a half win each time—you only see both extremes, win or lose. Variance is calculated as the average (or expected) squared difference between an outcome and the average outcome. The square root of that, the standard deviation, is usually more intuitive. If you win a dollar whenever you win the flip, and lose a dollar whenever you lose, you know in the long run you’ll break even, but the standard deviation is one dollar since you will always either gain or lose a dollar every flip. How many flips to be confident you’ll break even? We can estimate the standard error, which is the standard deviation divided by the square root of the number of flips. If you flip 100 coins, the standard error is 10 cents—you aren’t guaranteed to break even, but on average you should be within 10 cents. Note: this is just an average, and averages can be very misleading. Since you always win or lose a dollar, you can never be up or down 10 cents. In this case, we’re averaging over lots of outcomes—breaking even, up/down a dollar, up/down two dollars, etc.—and it’s simply the case that you will most likely break even, so the standard error is nearly 0.

For a weighted coin, the outcome has lower variance. You will either win more often or lose more often, and because there are only two outcomes, you can predict which of the two is more likely as long as you know how the coin is weighted. What this also means is that as you improve your win percentage, it will become more and more obvious! Your variance can only go down, regardless if you’re better or worse than 50%.

How do we calculate the variance of Commander games? Overall, you could imagine Commander is just a weighted coin flip: each player has a 25% chance to win and 75% chance to lose. Ironically, this means that as you increase that win rate towards 50%, the variance increases! Because of this, it’s really hard to know if you’re increasing your win rate without playing a lot of games!

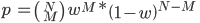

Say you play 10 games and win 4—is your true win percentage 25%, 40%, or 50%? This outcome is fairly likely for all those win rates, and we can explicitly calculate the likelihood of winning 4 games based on some hypothetical win rates. If p is the probability of your record, and we’ve played N games and won M times, we can calculate p as as a function of your true win rate:

There’s one additional trick here that may not be familiar if you haven’t taken

a probability class, the term  . There are many

sequences of games that amount to a 4-6 record. We need another term, called the

binomial coefficient, which counts the number of possible ways to have won N

games out of M total games, and that’s

. There are many

sequences of games that amount to a 4-6 record. We need another term, called the

binomial coefficient, which counts the number of possible ways to have won N

games out of M total games, and that’s  . This is

actually part of what makes being confident about records near 50% even more

difficult to nail down; there’s a lot of ways to win half your games and lose

half your games, so the probability of those types of records are a bit

inflated, regardless of your true win rate.

. This is

actually part of what makes being confident about records near 50% even more

difficult to nail down; there’s a lot of ways to win half your games and lose

half your games, so the probability of those types of records are a bit

inflated, regardless of your true win rate.

We can now compute some probabilities. The probability of 4 wins and 6 loses if you have a true win rate of 25% is 0.15. That means you’d expect this type of record about 15% of the time. If your true win rate is 40%, you’d expect this record slightly more often—about 25% of the time. If your true win rate is 50%, you’d expect the outcome about 20% of the time. Notice that these probabilities aren’t all that different; there isn’t one clear winner. In statistics, we often use an approach called maximum likelihood estimation (MLE): the most likely win rate is the win rate that maximizes the likelihood of the observed result. In this case, among win rates of 25%, 40%, and 50%, 40% is the maximum likelihood estimate.

But being the maximum likelihood estimate isn’t sufficient on its own to get a clear understanding of your win rate and variance! You need to always ask how confident you are in your estimate. There are technical ways to compute the error on your maximum likelihood estimate that requires thinking about derivatives, but I’ll spare you the calculus. Ultimately, as long as the likelihood of your maximum likelihood estimate isn’t that much more likely than the alternatives, you’re not very confident. In the example above, the result isn’t even twice as likely at a 40% win rate when compared to a 25% win rate.

After 100 games, you’d end up with a much bigger difference. If you won 40 games, the probability of that outcome with a true 25% win rate would only be 0.0004, whereas the probability of that outcome with a true 40% win rate would be 0.08! That’s 200x more likely, so while the maximum likelihood estimate is still 40%, you’re over 100x more confident after 100 games than you were after 10 games.

As you can see, you need to play a lot of games if you want to see if your win rate has actually improved over 25%. There’s an approach to decide how many games you should play to have a certain level of confidence, called power analysis, but I’ll spare you those details. Ultimately, you need to play a match up a large number of times, much more than 10, to have a confident estimate in your win rate.

How does Commander’s variance compare to the variance of 1v1 Magic formats? Let’s return to the example of 4 wins and 6 losses. Again, if your true win rate is 40%, you’d expect this record slightly more often—about 25% of the time. If your true win rate is 50%, you’d expect the outcome about 20% of the time. The 40% win rate is about 1.25x more likely than your baseline 50% win rate. Naively, you might think the 4-6 record is less informative in 1v1 then in Commander, given in Commander you’d know the 40% win rate is 1.67x more likely than your baseline 25% win rate. However, there’s a few reasons why that’s misleading.

First, a 40% win rate in Commander is much more impressive than a 40% win rate is disappointing in 1v1, so the comparison isn’t really fair. In Commander, you’ve increased your win rate by 15 points, whereas in 1v1 you’ve only decreased it by 10 points. As a percentage change in your win rate, it’s also much larger in Commander than in 1v1. You will largely need to worry about detecting smaller changes in your win rate, and small changes require a large number of games. With 10 games, you can’t ever score an exact win rate of 25%, and you’ll almost always (unconfidently) believe your win rate is 30% or 20% when your true win rate is really 25%. Even with 20 games, your most likely options are 20%, 25%, and 30%, and only once you get to 40 games do you get some granularity—22.5% and 27.5% win rates, which amount to a 10% change in the baseline, are now options. In the same number of games, 1v1 players can resolve changes half as small!

Second, unlike in 1v1 Magic, where you may have a dozen match ups you need to care about, in Commander you have much more. We can go back to the binomial coefficient to estimate just how many. The lower bound is that each opponent in your four player pod plays a unique deck, so we need to calculate , where N is the number of decks and M is the number of opponents. In 1v1, if there are 10 decks, there are 10 match ups, or 20 if you consider whether or not you’re on the play or the draw. In Commander, there are 120! Factoring in seat order, you have at least 2880! While not all match ups are equally likely, and while you might be able to ignore pods composed of only rarely-played decks, you have orders of magnitude more win rates to estimate, and each estimate is going to take a lot of games. The secret to solving this problem is using inference; you should learn something about playing a match in first seat from playing it in fourth, and you should learn something about playing combo decks in general from each combo deck you play against. Just like in machine learning / artificial intelligence research, the real strength comes from a player’s ability to generalize from the data they have on the matches they’ve played to matches they’ve never played before, and that’s an issue of player skill and knowledge.

Third, because of the first two points, no Commander tournament outcome is going to be strongly consistent with your long term win rate in the true metagame, so all the work you need to do to be confident in your performance can easily be for naught. In 1v1, you may see a bad match-up a little too often in an 8 round tournament, and rightfully attribute doing poorly to your bad luck. In Commander, there are almost always less rounds, and now orders of magnitude more match-ups. The best you can hope for is good luck, hitting more than one pod where you’re at an advantage. You will almost never experience a “representative” tournament. This is fully ignoring the impact of Swiss pairings—which will push more and more people to observing win rates close to the baseline. This means you’re more likely to observe a lower win rate in a tournament with Swiss rounds than in your practice games (unless you practice via Swiss tournaments, which 1v1 players can do rather easily on MTGO and Arena).

Lastly, when it comes to testing changes to your deck list, the singleton rule is a statistical killer. If I want to swap one set of a 4-of for another 4-of in Legacy, I can get a feel for the swap quickly because I am very likely to draw the new 4-of from my 60 card deck in any given game. In Commander, swapping one card for another may not have an impact for a long time; most of your games will not provide any data on the impact of the swap. Only the games in which the card shows up matter, and unless it’s a card you will frequently tutor for, that won’t be a large percentage of your games. This is why it can be so difficult to decide if a swap of a removal spell, mana rock, or counterspell for different versions of the same effect is having an impact. The games when you draw the new card are few, and the games when the new card meaningfully differs from the card it’s replacing will be even fewer. Even if one is objectively better, it could take thousands of games to be sure.

What does Commander’s variance ultimately mean for its players? It is unfortunately very difficult for a Commander player to estimate their true win rate in a blind metagame, and it’s especially difficult to understand how those win rates will change as you make single card swaps in your list.

Your best bet is to get very good at the inference component of the game: determining how to play in a given pod given your past experiences with your deck. You also need to gather as much diverse data as possible, so that your inferences can cover as many situations as possible. While it may be very difficult to predict what your win rate in a given tournament will be, you’re able to increase the likelihood that you can navigate a given tournament to your deck’s maximum potential by understanding how to play the pod given the deck you’ve brought. It will also let you predict how a single card swap may affect game play better, so that you can be more confident about swaps without having to accumulate an absurd amount of data with each new set release.